|

Click on top to return to List of Suspects

Click on bottom to return to

List of Suspects NBC

|

|

|

|

Marriage: (1) Margery Nelson (Sep 5. 1980 - Dec 27. 2000, his death) Brother: Warren Francis Link (Mar 6. 1939 - Apr 28. 2000) |

|

|

Above

right: William Link ca. 1951, Cheltenham High School |

|

|

Born on December 15. 1933 in Elkins Park, Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, William Theodore Link Jr. was the son of Elsie Roerecke

(Aug 16. 1898 - Jun 2. 1974),

stenographer at a NY Broker's office, and

William Theodore Link (Jul 28. 1892 - Nov 17. 1951) *, a textile broker. He grew

up in Elkins Park, a suburb of Philadelphia where he had a happy childhood and loved his parents. “I think reading is where it started. I wanted to read when I was four or five years old. In those days, that was discouraged. Now, parents—mothers—teach their kids at home. So I had to wait until I could read, and then I started reading all the Hardy Boys books, which are still being consumed today. Those were mysteries. Then I read all the typical childhood books. My mother had read to me when I was a kid—I remember 'The Little Engine That Could'. I also drew my own comic books. I’m from that generation; we were huge comic book addicts. I remember taking trunks of comic books to summer camp. I wish I had saved them. My mother threw them out. I was always interested in stories, even before I could read or write. I hid mysteries. I remember when I was in the Cub Scouts, a friend of mine’s father read mysteries and kept them. I used to borrow mysteries from him.” Then pencil in hand he drew his own comic books with his own super heroes. Later, he graduated to writing mystery short stories. At 10, he was already reading Weekly Variety. |

|

|

“I went to Shoemaker Grade School. Dick

went to West Oak Glen School. He lived right outside of Elkins Park. But

in junior high school, the first year, a lot of classes merged from

other schools. I was told to look out for a tall guy who loved mysteries

and did magic. He was told by his friends to look out for a short guy

who loved mysteries and did magic. We literally met at lunchtime on the

first day of junior high school and became instant friends. We shared

those interests—that was the foundation of our friendship.” So as of 1946 they began writing together soon after, writing sketches together at summer camp. They also shared hobbies. “We would each read two or three mysteries a week and trade the ones we particularly liked. That was really our entrance—Dick’s and mine—into a love of mysteries, which taught us a lot about structuring stories.” Each’s tastes were formed by cherished sessions with Captain Marvel, Superman, Saturday afternoon serials, Walt Disney, Abbott & Costello, John Dickson Carr, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Ellery Queen, Erle Stanley Gardner and such radio shows as Jack Armstrong, Inner Sanctum, Lights Out and Suspense. Early TV wasn't left out and Bill was totally hooked on Barney Blake, Police Reporter (NBC, Apr 22. - Jul 8. 1948). At Cheltenham High School, they created radio scripts. Bill and Dick convinced their parents to buy them the type of wire recorders popular after World War II. Soon after that, they switched to tape recorders—because you could edit tape. Wire was difficult to handle and impossible to edit. Putting together a jury-rigged repertory company, the teen collaborators started writing their own radio scripts. Levinson stated: “We started writing radio shows and had our friends over to the house to do these dramas. And, as Mike Nichols said about Broadway, it's a great way to meet girls. So they'd come over and they'd act. We adapted 'Two Bottles of Relish'; we adapted 'Donovan's Brain'... with his brother blowing into a straw to get the bubbling effect.” William added “At the time, motion picture music was just starting to be recorded, and we used those scores. We also bought professional sound effects downtown in Philadelphia so we could include trains, traffic, and so on. In a way, we were doing on a small scale what we’d end up doing later in our careers: producing what we’d written, using our friends—essentially shanghaiing them—on Saturdays when they’d rather be out playing football or doing something else.” |

|

|

The duo wrote “gloomy” short stories inspired by Poe and O. Henry, and

even had an original musical comedy staged during their senior year.

Fascinated by the mystery genre, the high school classmates regularly

mailed detective stories to major magazines like

The New Yorker and

The Saturday Evening Post.

Unsurprisingly, the rejection slips came back just as regularly. Before all that, Link had a brief brush with Hollywood. When Dragnet debuted on radio in 1949, he recognized its iconic opening notes as identical to the theme from Miklós Rózsa’s 1946 score for The Killers. He wrote to Dragnet composer Walter Schumann, who replied, “Yes, Mr. Link. With Mr. Rózsa’s permission, I took the theme from The Killers. Keep listening to Dragnet.” The duo actually did parody of the popular radio show, Dragnet. Later, when Variety reported that Rózsa’s publisher was suing Schumann for plagiarism, Link dug out the letter and passed it to his father, who relayed it to their attorney, and eventually to Rózsa’s publisher. After Rózsa won the case, Link was treated to a stay at the Plaza Hotel in New York and received tickets to every Broadway musical then running as a thank-you. (5) They also wrote the school musical Election Time, an original musical comedy that is still remembered at Cheltenham High School. It’s become something of a legend.Unfortunately, Bill's father died (1951) during his last year of high school. Dick’s mother died the following year, during their first year of college. |

|

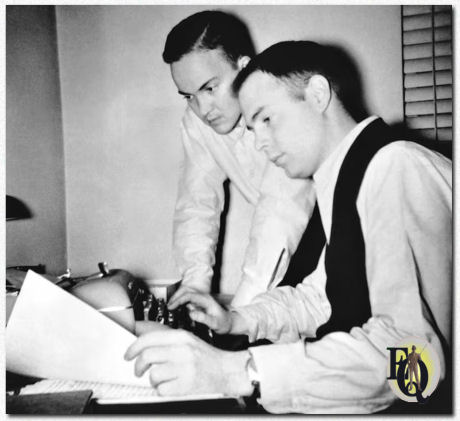

Above: William Link (L) and Richard Levinson, collaborating when they were students. |

|

|

“To hedge our

bets, we both got accepted into the Wharton School of Commerce and

Finance, which was then—and still is—the top undergraduate business

school, followed by Harvard for the MBA. That was a real eye-opener. We

hedged our bets because in those days, if you told your parents you

wanted to be a writer, they thought you meant a horseback rider. Writing

wasn’t considered a viable career. My mother, though, was very

supportive. It came down to: 'What makes you happy? Do what you

want—I’ll back you.' ” Levinson and Link attended the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, though they had little interest in business. Long before cinema studies became a formal discipline, both were already analyzing films and teleplays. Their favorite writer-director was Billy Wilder—they were obsessed with everything he created—and their favorite teleplay writer was Paddy Chayefsky. They contributed to Penn’s humor and literary magazines: writing film criticism for The Daily Pennsylvanian, founded the university’s Highball humor magazine, and wrote some of the lyrics for five Penn's Mask and Wig musicals. These were huge, professional-level productions. The direction, orchestra, and scores were all original, and they cost around $100,000 per musical—which was a lot of money in the 1950s. That money came from Penn football receipts, as Penn had a big team back then. “We loved that—writing and seeing our musicals produced. They even went on the road during Easter and played at the Forrest Theatre in Philadelphia, a legitimate venue where shows like 'Oklahoma!' had played. I remember our best show was a spoof of motion pictures called 'Vamped'. Variety’s reviewer said, “This book is as good as anything on Broadway right now.” We thought, 'Wow—what are we doing in business school?' ” “What really caught our attention was what is now called the Golden Age of Television. We realized that mature, interesting dramas could be written for television, so we started writing television scripts while still at Penn.” They now had sold their first short story, “Whistle While You Work”, to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, which published it in the November 1954 issue. It is a charming little story about a henpecked mailman who eagerly anticipates escaping his stifling home, where his overbearing wife rules the roost. Over several days, a series of oddly addressed letters—blue envelopes with black borders—arrive in his mailbag, each one addressed to a different woman. Soon, each woman who receives one of these letters is found brutally murdered. Although it would take four years to sell another story, the joint direction of their lives had been established. They even were allowed to collaborate on a senior thesis, since it was permitted to submit “publications,” so they turned in three screenplays—all of which were eventually sold to Alfred Hitchcock. After they graduated, the school closed that loophole. (5) “According to them show business was not a business.” They both earned a degree from the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business and decided to act quickly. |

|

|

“The week after we

graduated, we went to New York. We had a contact at the William Morris

Agency, which was probably the most powerful entertainment agency at the

time. We met Harry Kalcheim, the father of a friend of a friend. He was

one of the great agents—he produced the Texaco Star Theater with Milton

Berle and represented a lot of major talents. He was very nice and

signed us for two years as writers with William Morris. I was ecstatic. I took the train home, walked in, and found a letter on the mantle. It was from Uncle Sam—an invitation to join the armed forces. What a blow. At the time, there was universal military training—two years active duty, followed by four years in the reserves. Dick was six months younger, and by the time he went in, a six-month program had just started—but I had to serve the full two years.” Link served in the United States Army from 1956 to 1958. During their Army service they continued collaborating on stories by airmail. Levinson served briefly, then worked at what is now NBC10. After Link returned to civilian life, the childhood friends headed to New York, only to discover that the golden age of live anthology drama had passed. When they got out, they were shocked to find that all the great New York dramas were gone. Television had moved to Hollywood—private-eye shows, Westerns, sitcoms. Nothing with the depth of the Chayefskys or Vidals. To make ends meet, they sold short stories to publications like Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Playboy, and others. Two of their scripts were produced by General Motors Presents, a Canadian anthology series aired by the CBC. |

|

|

Their American television debut was a strong one.

Their script for Chain of Command,

an Army drama set in the South, was produced by

Desilu Playhouse and hailed by

TV Guide as one of the best

shows of the 1958 - 1959 season. Levinson and Link were just twenty-four

years old. The pair decided to pursue their dreams in Hollywood and

moved to Los Angeles. Levinson flew out first, while Link drove cross-country with his close

friend Mike Rosenfeld, who would later become a William Morris agent and one

of the founding partners of Creative Artists Agency (CAA). The move was a culture shock for two intellectual guys from Philadelphia and New York, suddenly surrounded by garden apartments, purple lights in the trees, people in Bermuda shorts at Christmas, car culture, and poorly designed freeways. The city was strange. The art scene was limited, there was no decent symphony, only one jazz club, and maybe five good restaurants. “We were used to the great restaurants in New York. Out here, there was Chasen’s, Scandia, LaRue, Perino’s—and that was about it. We couldn’t even find a good steak. The one at Chasen’s was awful. We thought, “Where do they get these steaks—from South America? But work came first. We realized this had to be our home, and it turned out to be almost immediately. As soon as we got off the plane, we were under contract. Four Star Television—Four Star was the number one television producer in those days.” |

|

|

Success in television came quickly for the duo—their

first year brought in $50,000, a small fortune at the time. According to

Link, it impressed his mother and made his brother jealous.

Over the

next decade, they freelanced steadily, writing episodes for a wide range

of mystery and drama series, including

Johnny Ringo,

Honey West,

The Fugitive, and

Burke’s Law. Still, the work lacked fulfillment, so Levinson and Link chose to divide their time between New York’s theater scene and Los Angeles’s television industry. “Then there was a writer’s strike in 1960. We were amazed because Christopher Conover walked into our office and said, 'Get out of here.' We asked why—we had just joined the Writers Guild—and he said, 'Well, your guild is out on strike.' We couldn’t believe it. We had to leave our office at Four Star. The strike lasted almost six months. We went back to Philadelphia and worked on a novel. We figured we could write for live television—even during the strike.” Enter Lieutenant Columbo, the Los Angeles police detective known for wearing a shabby raincoat, smoking cheap cigars, and snaring murderers by playing dumb. Columbo (played by Burt Freed) first appeared in the Levinson and Link-penned mystery "Enough Rope", which aired as a one-hour live broadcast on The Chevy Mystery Show on July 31. 1960. An expanded version of the mystery would go on to become a hit theatrical production ** in 1962, this time entitled Prescription: Murder and featuring Thomas Mitchell as the meandering Lieutenant. The play opened in San Francisco with Joseph Cotton as Dr. Ray Fleming, the suave psychiatrist who cooks up the ideal way to kill his wife. Agnes Moorehead, played his ill-fated spouse. Academy Award—winning actor Thomas Mitchell was chosen to portray Lieutenant Columbo. “Mitchell was terrific, but we didn’t get good reviews,” Link said. “It needed work. But it went on tour for twenty-five weeks in the United States and Canada, and it made a fortune. ... They loved the Columbo character. We thought he was a character of secondary importance.” In 1961, they began a fruitful association with director-turned-TV-host Alfred Hitchcock. The duo contributed two scripts to the half-hour Alfred Hitchcock Presents and five to The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. “Dear Uncle George,” a 1963 episode, featured Gene Barry as a man who kills his wife. Five years later, the actor would play a similar role in the TV movie version of Prescription: Murder (NBC, Feb 20. 1968) when the successful mystery play was turned into a television movie. The Columbo part was made famous on television by Peter Falk, whose comic timing brought life to the idiosyncratic homicide detective. Beginning in 1968, Falk played the part off and on until Columbo Likes the Nightlife (ABC, Jan 30. 2003). From it's start the formula was set. The concept behind Columbo is that it’s an inverted—or open—mystery. Unlike the classic whodunit, the audience witnesses the murder from the start. We already know who did it. The real suspense lies in how Columbo is going to catch the killer—a “how’s-he-gonna-catch-him” rather than a “whodunit.” Steven Spielberg, the “boy genius” on the Universal lot who was entrusted with directorial duties on "Murder by the Book", which would be selected as the opening episode of Columbo’s first season. It opened doors that the then-24-year-old swarmed through to establish himself as one of the leading filmmakers of the 20th and 21st centuries. As for how Columbo got his name—Link and Levinson were asked that question for years, and for years they gave various answers. But in a 2011 interview (5), Link revealed what he had come to believe was the true inspiration behind their detective’s iconic name. It came from one of Billy Wilder’s greatest films, Some Like It Hot, which premiered in 1959. Levinson and Link were there on opening day. They studied the screenplay closely and rewatched the film countless times. Only recently did Link notice what had been hiding in plain sight: the gangster chasing Curtis and Lemmon’s characters, played by George Raft, is memorably named “Spats.” His full name? Spats Colombo. |

|

|

The first L&L Hitchcock script, “Services Rendered,”

included a character named Mannix (they had a high school chum named

William Mannix). They liked the name well enough to use it for a

detective series. The pilot was rewritten, and they didn’t like that.

They left Mannix to go to

Universal. They usually didn’t like to stick with shows—set them up,

launch them, bring in the right writers, and then move on. They always

had other projects in mind. “On

Mannix, Mike Connors was terrific. We liked him a lot.”

The two-fisted private eye,

Mannix lasted eight seasons (CBS, 1967 - 1975). Based on Cat of Many Tails by Ellery Queen, NBC produced Ellery Queen: Don’t Look Behind You in 1971. The script was written by Richard Levinson and William Link, who were credited under the pseudonym “Ted Leighton” (their combined middle names) because they disapproved of changes made while they were vacationing in Europe. They were right—it’s an easily forgettable 96 minutes. |

|

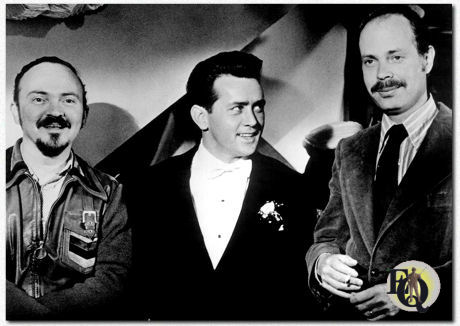

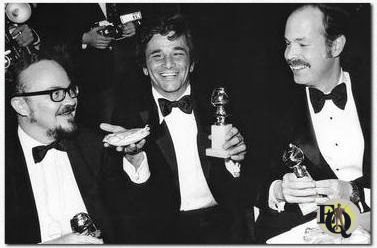

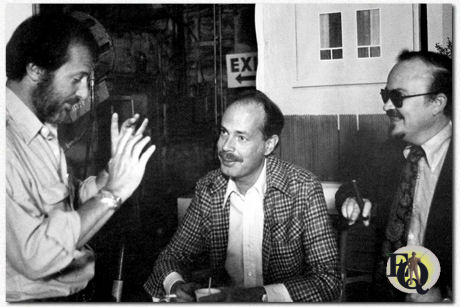

Above left: (L-R) William Link, Martin Sheen and Richard Levinson in the 1970s. Martin Sheen would play both in That Certain Summer (ABC, Nov 1. 1972) the first gay themed show to win an Emmy, and again in The Execution of Private Slovik (NBC, Mar 13. 1974). Both of those were written and produced by Link & Levinson. Above right: William Link, Peter Falk, and Richard Levinson receiving the Golden Globe, January 28. 1973 (for Best Performance and Best Series in 1972) (Photograph, Hollywood Foreign Press Association). |

|

|

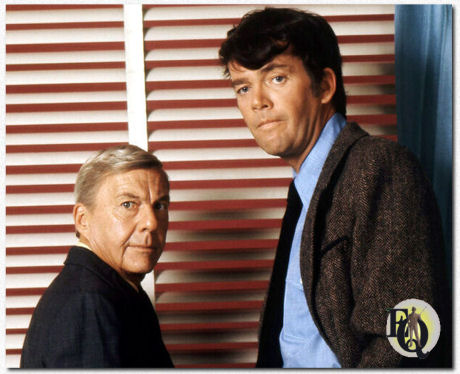

They launched the much-admired but short-lived

Adventures of

Ellery Queen (NBC, 1975 - 1976).

Link explained: “

'Ellery Queen' was based on the novels we’d read as kids. We won

the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Mystery Movie of the Year. At the banquet

in New York, an old gent grabbed me and said, 'I am Ellery Queen.'

It was Fred Dannay. The name was a pseudonym for two cousins. His cousin had

died. We spent a day with him in Larchmont, Long Island. It was wonderful. We got Jim Hutton and David Wayne—he was great as the father. It really became the template for 'Murder, She Wrote'. The clues in 'Ellery Queen' were too difficult. We realized we had to make them easier so the audience could feel clever and keep watching. We were up against 'Sonny and Cher', which had just reunited and became a national event. It was a tough time slot. But we had fun. Elmer Bernstein did the theme. We set it in stylized 1940s New York—one of our favorite periods. Watching some of the old shows, they still hold up.” It also didn't help that Brandon Tartikoff, head of NBC, didn't like the show, it got cancelled. |

|

Top: In Ellery Queen there was remarkable chemistry between Hutton and Wayne, forming a robust and convincing duo, seamlessly complementing each other's performances. Above left: In September 2010 a DVD box set was released with the complete pilot and an Ellery Queen featurette, with participation by series Co-Creator William Link. David Lambert of tcshowsdvd provided this sneak preview. Above right: "The Adventure of the Sunday Punch" (NBC, Jan 11. 1976), an episode of Ellery Queen with Ken Swofford and actress Maggie Nelson. She would marry William Link in 1980. |

|

| One of the recurring characters was in fact Vera, as the secretary of Frank Flannigan. She was played by Maggie Nelson. Under that name she also played in an episode of The Eddie Capra Mysteries (NBC, Dec 8. 1978) ... On September 5. 1980 Margery Nelson (Apr 3. 1939 - ) and William Link were married in Manhattan, NY. As Margery Nelson she continued to work both as an actress and producer. She is the daughter of Alexander R. Nelson (Dec 3. 1905 - Oct 23. 1990), a NY lawyer and Doris H. Siegel (1912 - bfr. 1983). | |

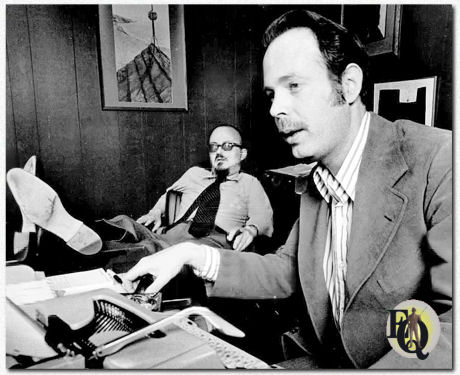

Above: Bill Link and Dick Levinson, make up one of a number of successful television writing teams. Their latest efforts going into the new Ellery Queen series (APN Illustrations, Jul 27. 1975) |

|

Above left: (L-R) James Goldstone, Richard Levinson and William Link. Goldstone directed Rollercoaster (Universal, Jun 17. 1977) for which our duo provided the story/screenplay. Above right: Levinson and Link with their 1980 Edgars for Murder by Natural Causes in the category "Best TV Feature or Miniseries". |

|

|

He was nominated for Broadway's 1983 Tony Award as Best

Book (Musical) with collaborator Richard Levinson for Merlin

(Mark Hellinger Theatre, Dec 10. 1982 - Feb 13. 1983). “In a way 'Ellery Queen' really became the template for 'Murder, She Wrote' because, looking back, the clues were too difficult—they were too ingenious. And we learned: give the audience a chance. It should really be a fair contest between us and them. That’s why, when we finally did 'Murder, She Wrote' with Angela, we made the murders a little easier to guess so the audience could figure them out. After patting themselves on the back, they'd come back and watch us again the next Sunday. I mean, there was a method to our madness—and our “dumbing down,” as it was. But 'Ellery Queen' was a very good experience.” The creators of Murder, She Wrote were initially asked by CBS executive Harvey Shepherd to develop a mystery series for actress Jean Stapleton. Although they wrote a pilot script with her in mind, she didn't understand it and ultimately declined the role. “We had always been fans of Angela Lansbury. We heard she was available, but the television audience really didn’t know her. She was a movie person. She was in Liz Taylor’s first movie, playing the older sister. She had done a lot of great work. She was also the original Auntie Mame on Broadway. We loved her. But we figured, if we took her name into Harvey Shepherd, we were dead— he was going to kick us out of his office. But we had no one else, and we thought, 'She’s English, she comes from that whole British murder mystery tradition. She’d be really good. She’s a fine actress.' So we thought, 'What do we have to lose?' Well—the series. But what the hell. We walked into Harvey’s office at CBS City and floated her name. His eyes lit up. It turned out, serendipitously, that his father—who I think was a butcher in Long Island—had been part of a big theater-loving family. They went to see all the musicals. They were huge Angela Lansbury fans. Harvey said, "If you can get her, you’re on the air.' ” After reading both their script and another offer from Norman Lear, Lansbury chose Murder, She Wrote. Her casting proved pivotal, as the show's success depended heavily on the right lead. The producers credited her performance as essential to the series becoming a television classic which ran for twelve seasons (1984 - 1996). |

|

Richard Levinson, at age 52,

died of a heart attack on March 12. 1987. A heavy smoker—three packs a day, sometimes four

under stress—he had started as a teenager, with Link by his side the day

he lit his first cigarette. Link always feared it would one day kill his

friend, and Levinson knew it too—“but he was hooked.” His death devastated William, who sought therapy to cope and find a way to keep writing. Even then, he felt his partner’s presence. “I think Dick sits on my shoulder, telling me, ‘Bill, you can do better with that line.' ” Link continued his writing and producing career in many media. In 1991, in tribute to Levinson, he wrote the script for the 1991 TV film The Boys, starring James Woods and John Lithgow. He was a frequent contributor to such mystery fiction publications as Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. Link also was executive story consultant on the short-lived science fiction/detective series Probe in 1988. His post-Levinson TV work includes The Cosby Mysteries (1994 - 1995), starring Bill Cosby. In 1995 Richard Levinson and William Link were inducted into the Hall of Fame. In 2010, the specialist mystery publishing house, Crippen & Landru, released The Columbo Collection, a book featuring a dozen original short stories about Lieutenant Columbo, all written by Link. In 2021, a further collection of stories, Shooting Script, was edited for C&L by Joseph Goodrich. |

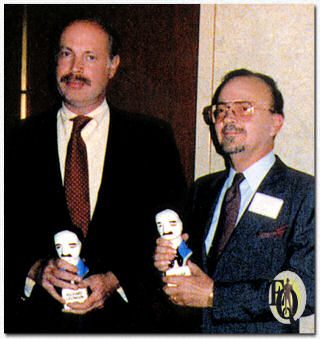

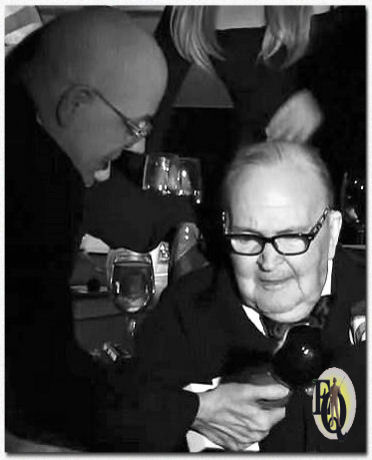

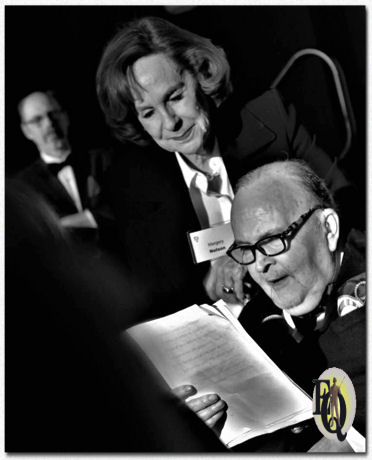

Above left: In 2018 MWA offered William Link the Grand Master Edgar, Joseph Goodrich Above right: Bill, aided by Margery Nelson, made an excellent acceptance speech (glorious photo by Peter Rozovsky). Click on the photo to hear the full speech. |

|

Living in Beverly Hills, Los Angeles with his wife Margery and their

little Yorkshire terrier Winston, he continued to write every day—seven days a week. No

longer for television, but he continued crafting mysteries and

short stories. And he sold every one. Although Link will forever be associated with Columbo, his final years featured an ugly legal battle with NBC, Universal over 40 years’ of unpaid profits from the successful series. A jury initially awarded Link and the heirs of Levinson more than $70m in 2019, but the decision was swiftly overturned and, as far as we know, a new trial has yet to take place. |

| William Link died from heart failure in Los Angeles, on December 27. 2020, twelve days after his 87th birthday. The family helped Link mark his birthday by playing YouTube videos of interviews in which he recounted his long career. He loved it. It was the best birthday present he could have gotten. |

|

|

Notes: * After living his entire life as a non-Jew, Link discovered he was Jewish around 2011. His grandfather Frank Edward had abandoned the family when Link’s father was just 13 years old. As a result, Link’s father grew up with little knowledge of his family background. On his mother’s side, the lineage traced back to the Huguenots, and she spoke German. His father was raised on the Lower West Side of New York (first clue) and became a self-made man, working as a textile broker (second clue). Since the textile industry was predominantly Jewish, he even picked up some Yiddish (major clue). Despite these hints, Link believes his father never realized he was Jewish—and Link himself was raised outside of the Jewish faith. (5) Link's niece, Amy, examined a suitcase that William Theodore had left to his son and which had been stored in their attic. When she opened it in 2011, she found that it contained genealogical research and documentation compiled by William Theodore during World War II. Through this discovery, Amy learned that Link’s paternal grandparents were Jewish. ** They had worked on another Broadway musical providing "additional material" for the short-lived Vintage '60 (Brooks Atkinson Theatre, Sep 12. - 17. 1960). All dates for movies are for the first US release. All dates for TV programs are original first airdates. All dates for (radio) plays are for the time span the actor was involved. Programs, facts or dates in red still need confirmation. |

|

Click on Uncle Sam if you think you can help out...!

|

|

Other references

Additional video & audio

sources |

|

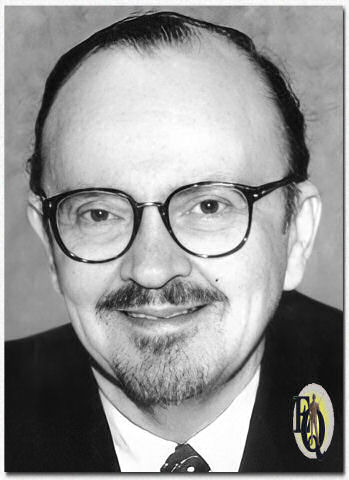

This profile is a part of

Ellery Queen a website on deduction.

The person above produced the Ellery

Queen TV series in 1975-1976.

Click Uncle Sam if you think you can help

out...! Many of the profiles on this site have been compiled after very careful research of various sources. Please quote and cite ethically! |

|

Page first published May 1. 2025 Version 1.0 - Last updated May 2. 2025 |

b

a c k

t o L i s t o f S u s p

e c t s

b

a c k

t o L i s t o f S u s p

e c t s

b a c k

t o L i s t o f S u s p

e c t s N B C

|

|

| Introduction | Floor Plan | Q.B.I. |

List of Suspects | Whodunit? | Q.E.D. | Kill as directed | New | Copyright Copyright © MCMXCIX-MMXXV Ellery Queen, a website on deduction. All rights reserved. |